Organisational complexity is an acknowledged by-product of scale. Formal hierarchical structures are needed as organisations grow to ensure smooth functioning and a focused approach towards achieving common goals. Globalisation has compounded this complexity by introducing additional variables such as distinct local cultures, practices, and employee psychological makeup.

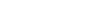

Most modern-world organisations emphasise these formal structures and hierarchies primarily as a means of establishing status and the flow of authority. Such structures are considered so necessary and are so ubiquitous that one cannot imagine a truly flat structure with little to no hierarchy, even in an early-stage startup. Consider a ubiquitous hierarchy structure that one may see at a large Indian IT/ITES company:

Irrespective of the organisational scale, ensuring common objectives are met depends on a clear understanding of the formal structure and submission to it.

Status disagreement and its causes

Disagreements over status are common, however. The motivations for such disagreement are fairly obvious – status defines an individual’s relative standing in terms of respect and deference from others. Motivation, though, does not equate to cause, one of which is the employee’s perception of self. Intuitively we know that people pay more attention to and give more weight to their own efforts and contributions, which is backed by research on motivated perception (Kunda 1990, Epley et al. 2006). This motivated perception often leads to an inflated perception of their status relative to others, resulting in status disagreement, particularly upward status disagreement (USD), a situation in which each individual ranks themselves higher in status than the other. The field of psychology suggests that the biased, selective, and malleable nature of motivated perception causes humans to even visualise things that do not actually exist. Apply this to a subjective situation of, for example, evaluating the contribution of an individual to a team project and you can see how the scenario can be a figurative minefield full of status disagreement.

A clear and objective formal hierarchy should limit the occurrence of USD within organisations and facilitate collective action (Simon 1962, Tushman and Nadler 1978, Nadler and Tushman 1997). Thus, a senior vice president ranks above a vice president, who ranks above a sales director, and so on. The paradox seen in the real world is that these formal structures and job titles are often themselves the source of disagreements over who ranks above whom and commands more status. For the sake of abundant clarity, organisations drive home vertical hierarchies through visual representations of seniority through organisation charts that show people exactly where they rank within an organisation. Research by Professor Nikhil Madan and his co-authors questions this innate assumption. The research proposes that USD can actually occur and be exacerbated due to the presence of formal hierarchies meant to mitigate it while identifying key scenarios in which USD is more likely to occur. One reason is the disconnect we often see between formal rank and the on-ground status of individuals. For example, the sales director of a division that contributes a 40% share of total company profits may perceive that she has a higher status than a senior sales director of a division that contributes only a 20% share, especially if she heads her division. Meanwhile, the senior sales director would believe that the organisation chart dictates status, making him higher ranked. In the event that these two individuals have to work together on a task, a conflict would arise, especially in cases where the relationship is one of competitive interdependence and less so in a situation of cooperative interdependence or complete independence of goals.

Besides contribution-based disagreements, another source of status disagreement is the fact that as much as organisation charts may depict hierarchies as vertical ladders, they are not – rather, hierarchies are often made up of many branches and nested sub-units. For instance, a multinational might have several directors in charge of different teams or sub-units across different countries. A global vice president may have a higher rank than a sales director in the organisation chart, but the perception of rank will be driven by how far down each person ranks in their unit. A director at the top of her country’s organisation chart will perceive herself as senior to the vice president, who ranks below the CEO, president, and senior vice president in his organisation chart. Similarly, a vice president of finance reporting to the CEO would perceive himself as higher-ranked than the vice president of technology who reports to the COO. Such disagreements are benign if we compare positions functionally disconnected from each other. The more their functions overlap and the more they have to work together, the more tangible the conflict.

If formal hierarchies contribute to status disagreement and conflict, flatter organisations must be the answer, correct? Not exactly. Fewer defining vertical and horizontal boundaries, intended to foster a greater shared purpose, clearer lines of communication, faster decision-making, cooperation, and camaraderie, can actually increase the chances of USD. The reason is people’s fundamental motivation to compare themselves with others, and the absence of formal structures may make them draw on informal cues such as race, gender, or seniority cues such as age, regardless of whether they are appropriate or not, in making their judgements about status, thus aggravating the problem. One tangible example is a prominent Indian steel company that collapsed multiple layers of hierarchy numbering 10-12 levels into five. All existing white-collar employees were slotted into one of these levels (numbering from 1 to 5) leading invariably to disgruntlement from employees who felt short changed. Expectedly, criteria such as tenure, age, location, departmental size, etc., then came into play when perceptions of seniority ran counter to the actually assigned managerial rank.

Challenges and implications

USD rises as organisational structures become more complex, geographical spread increases, the workforce becomes increasingly diverse, and businesses/startups emphasise egalitarianism, which are realities of today’s times. Organisational scientists have documented the implications of USD − research by Bendersky and Hays (2012) shows that USD may result in a rise in interpersonal and status conflicts, such as attempts to assert dominance, forming opposing coalitions, and making political plays. USD may also prioritise individual goals over collective objectives.

Proposed solutions

Professor Madan’s research identified some relatively simple solutions organisations could consider to limit such disagreements. The first step to solving a problem is to acknowledge it. Hence, the different formal and informal cues that impact perceptions of status within the organisation need to be recognised. Due care and prior planning in this regard before asking individuals from different teams or regions to collaborate can help to anticipate USD. For example, cultural nuances play a big role in exacerbating USD. When, say, team members from a “tight” society like Japan are asked to work with colleagues or partners from the USA, which is a more egalitarian and “loose” society (see Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., ... & Yamaguchi, S., 2011), the ground is ripe for status disagreement and conflict. Proper and formal sensitisation can be a key mitigant in such cases.

Second, the research shows that the subjectivity involved in how individuals weigh different status cues contributes to differing perceptions about status and is a prior condition for USD to occur. Ensuring adequate localisation of company-wide culture and norms regarding the weights assigned to these cues reduces the chance of USD occurring. This requires a balancing act between a strong company-wide culture that allows employees from different locations or departments to appreciate the equal value of all parts while appreciating local nuances. An extreme case of organisation culture trumping other cues comes from the army where a subordinate who has high perceived informal status in the eyes of others because of his valued expertise (example, an experienced non-commissioned officer) is unlikely to engage in status conflict with his superior (example, a fresh Lieutenant in the unit) even though the superior has lower informal status. In this case, formal rank makes engaging in status conflict with the boss challenging and costly. Modern organisations though do not have such advantages of tight culture and what can help is a clear definition and communication of the company culture, and alignment of policies and actions with it.

Next, once again borrowing from the functioning of armies, the research suggests that strengthening uniform cultural norms can also be relevant when considering the potential for USD to arise even in less hierarchical organisations. The clearly defined rules, structures, and formal ranks in armies clarify who is in charge and allows for complex actions to be carried out efficiently and effectively. This is a nuanced point, though, as the authors point out − armies also have clear norms wherein local ranks and status take precedence over global ranks. For example, in combat missions, the leader in the field (local team) makes important executive decisions irrespective of rank without deference to his superiors who are not part of the operation (global team). This works well for armies because of the uniform and strong culture that all soldiers share, which allows for dynamic yet consistent switching in the importance given to different cues, even in evolving situations.

The research suggests that a strong company culture and values that are clearly defined, communicated, and understood (such as in the army) can counter the informal cues that lead to status disagreement and conflict even in flat organisations.

References:

Kunda Z (1990) The case for motivated reasoning. Psych. Bull. 108: 480–498

Simon HA (1962) The architecture of complexity. Proc. Amer. Philos. Soc. 106:467–482

Tushman ML, Nadler DA (1978) Information processing as an integrating concept in organisational design. Acad. Management Rev. 3:613–624

Nadler DA, Tushman ML (1997) Competing by Design: The Power of Organisational Architecture (Oxford University Press, Oxford).

Bendersky C, Hays NA (2012) Status conflict in groups. Organ. Sci. 23:323–340

Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., ... & Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. science, 332(6033), 1100-1104

Featured Faculty

Nikhil Madan