Personality: Fixed or Malleable?

Harnessing the power of self-nudging not only empowers personal growth, dismantles toxic patterns, and forges new habits but also catalyses organisational transformations, optimising performance, and fostering lasting cultural change.

Grit. Growth Mindset. Nudge. Atomic Habits. All popular books with a cult following, amongst those seeking to improve themselves, continually. All these books espouse just one simple truth. That, you are malleable. It is all about your mindset. The mindset to begin, to persist, even if you begin with small, tiny changes, for they will compound into the outcomes that you desire.

A rich body of research supports this proposition. According to the 1993 paper, "The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance", by Ericsson, K. Anders, Krampe, Ralf T., Tesch-Römer, and Clemens in the Psychological Review, expert performance is a result of an individual’s prolonged effort to improve performance and optimise that improvement through a long period of deliberate practice, rather than innate ability, or talent.

The underlying thought here is essentially the same. Personality is not fixed. It is malleable. All one needs to do is, incorporate small changes and stick with them, to improve performance and outcomes.

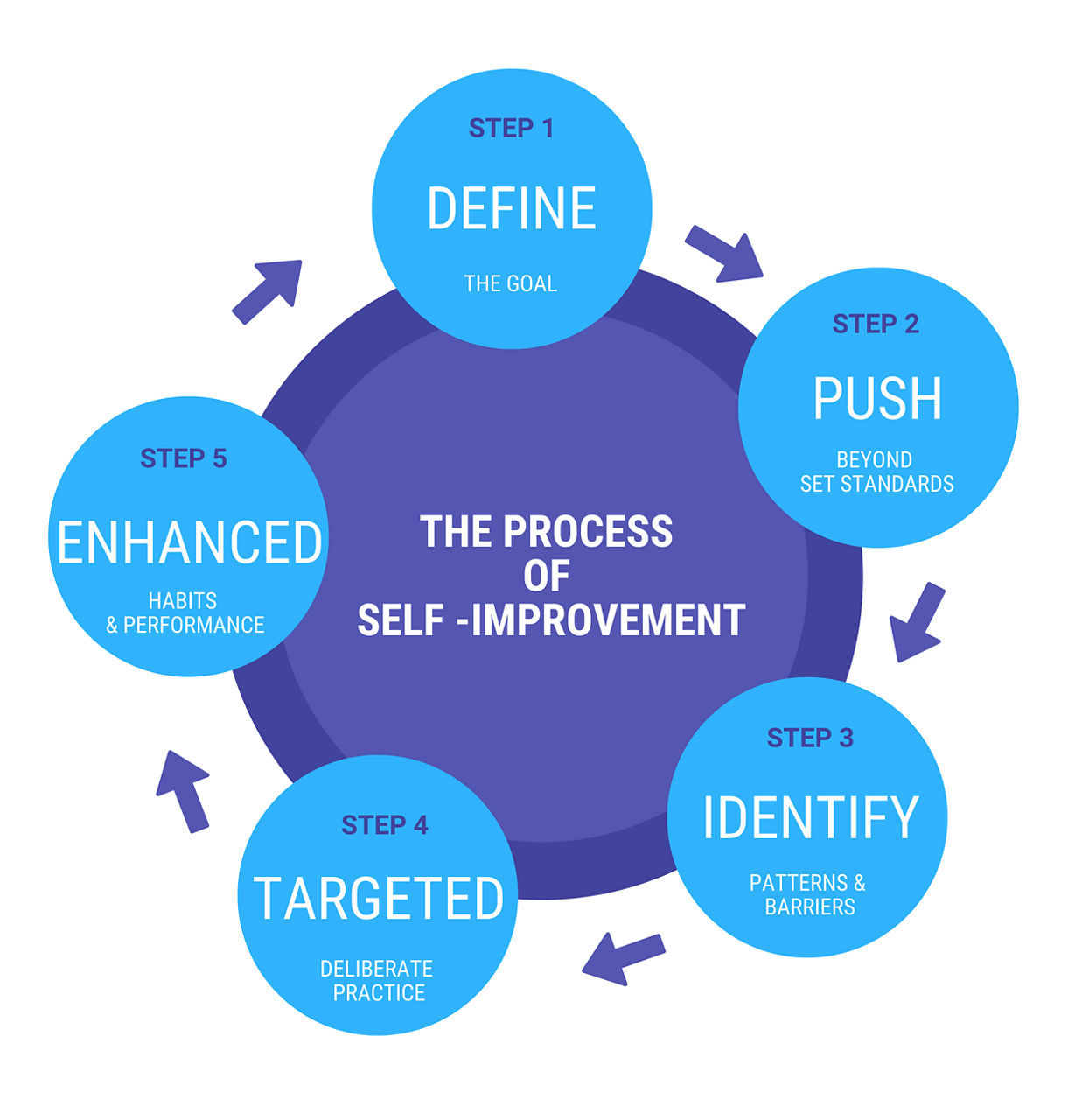

A Cycle of Self-Improvement

Ericsson went on to say that, merely practicing a skill repeatedly will not result in expert performance. It takes deliberate practice, defined as, "when individuals seek out new challenges, that go beyond their current level of reliable achievement - ideally in a safe and optimal learning context that allows immediate feedback, and gradual refinement by repetition".

Ericsson, in his 2012 book, co-authored with Jerad H. Moxley, "Handbook of Organisational Creativity", demonstrates this with an example. If the goal for an individual or a team in an organisation is to increase their typing speed, they should first begin by blocking a chunk of time during their most productive period in the day, and start typing, pushing themselves to type faster than their normal comfortable speed (Dvorak, Merrick, Dealey, & Ford, 1936). As they observe their efforts, they become aware of the keystroke combinations that are causing hesitations and slowing down their typing. They then try to overcome these problems with targeted practice.

Once they overcome these challenges, the cycle starts over. By identifying new problems, and then incorporating ‘deliberate practice’ into their routines to overcome these. This helps them improve their efficiency and performance, consistently and continuously.

Nudges

At the heart of deliberate practice to enhance outcomes is that push. The push that you give yourself, to improve yourself, to gain ground in the direction you have set for yourself, or to make high-impact changes in your life. It is that first tiny push that you give yourself that ultimately leads you to tap into, and fulfil your potential.

Developing a new habit or affecting a behaviour change can seem daunting. But we can make it easier for ourselves. Research in behavioural economics tells us that there is a way to give ourselves this push. A subtle suggestion - one that does not impinge on our freedom to make a choice – incorporated into our environment, that gently nudges us towards our desired outcomes, via a path of least resistance. By designing and structuring our environments to steer us in the right direction, we self-nudge, exploiting our cognitive flaws to counter our mental blocks.

Our cognitive capacity is limited, and contingent upon external factors. This ‘bounded rationality’ of the human mind, proposed by Herbert A. Simon, influences how we make decisions. Every day, we are faced with choices. From simple alternatives to complex decisions. Every time we are faced with a choice, there is a "choice architecture" intrinsic to it, notably, a structure and pattern to our decision-making and the set of alternatives that we choose from. Bounded rationality leads us to use heuristics or mental shortcuts in making these choices. In turn, choice architects manipulate heuristics and design environmental cues to nudge us towards the desired choice, by presenting it as the default choice.

For instance, you might want to prioritise an important task at work, or you might want to set aside a few hours every week to build on your job-related skills. You can create a distraction-free environment for yourself, where the task at hand becomes your default choice. You can do this by blocking ‘focus-time’ on your calendar, keeping your phone away, turning off notifications on your emails or anything else that will help create an additional layer, a barrier which increases the effort required to access these distractions.

“If you want to get people to do something, make it easy,” says behavioural economist and Noble Laureate Richard H. Thaler, University of Chicago. With the book, "NUDGE: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness" that he co-authored with Cass R. Sunstein, Harvard University, he popularised ‘nudges’. These nudges build on the flaws in human cognition, the mental shortcuts that lead us to make irrational and imperfect decisions, and act as interventions that influence our decision-making, and shape our behaviour, by changing the choice architecture and context of our decision-making, while keeping intact our liberty of choice.

Nudges can also be positive. Carol S Dweck, in her book, "Growth Mindset", talks of a high school in Chicago, which gives its students a ‘not yet’ grade instead of a ‘fail’, when they don’t pass a course. This is a mental cue which helps students understand that they are on a learning curve, and not let them feel boxed in and restricted with the stigma of being labelled a failure.

Impact

While at a personal level, self-nudging can help us negotiate internal conflicts over short-term costs and long-term gains, and make more rational and beneficial decisions, helping us chip away at our goals, break toxic patterns or create new habits. At an organisational level, one can drive efficiencies, improve and optimise employee and team performance, and affect a culture change that sticks. A straightforward instance of a behavioural nudge in the workplace would be this: you want to reduce the use of paper in the office, so, you cut down the number of printers to only one - a single printer in a little-used corner of the office. By making it a shared resource for everyone on the floor, and one that is not easily accessible, you are nudging your employees to start using digital documents, as the default choice.

The implications extend beyond individuals and organisations to policy and societies. To draw from the study, "Nudging, Shoving, and Budging: Behavioural Economic-Informed Policy", by Adam Oliver, welfare interventions designed to nudge social behaviour in beneficial directions, such as healthy eating and sustainable consumption, can create social change across several high-impact areas of health and environment.

Found this interesting? Build on these insights and analysis and elevate your knowledge with ISB Executive Education. Click here to find a programme that suits your needs.

-/MNI-innerpage-banner-updated.jpg)